“France: La Parité is an effective measure to achieve equality through law”

“Germany: Political parties encourage women''s participation through voluntary gender quota system”

“Sweden: Women appointed for positions that truly matter…”

The Women’s News (WN) launched a 9-parted forum on ‘Gender Equal Countries’ this April in order to observe Korea’s status quo in terms of gender equality and to draw a blueprint to make our society more gender equal. The forum covered all aspects of our society including labor, education, culture, environment, and national defense. The forum, which took place right before the inauguration of the new administration, set forth the goal to promote ‘gender equality’ as one of our national agendas. On Oct. 4, marking its 25th anniversary, the WN held a special forum with experts at Korea Dialogue Academy in Jongno-gu, Seoul. The practices from France, Germany, and Sweden were introduced to give an insight on where Korea stands in terms of gender equality and where to go from here. The attendees of the forum were as follows: Shin Pil-kyun, Head of Women’s Solidarity for a Welfare State; Kim Eun-kyung, Director of Sejong Leadership Institute; Kim Eun-ju, executive director of the Center for Korean Women & Politics; Choi Yeon-hyuk, professor at Södertörn University; and Kim Hyung-jun, professor at Myungji University. Cho Hye-yeong, editor-in-chief for WN served as the moderator.

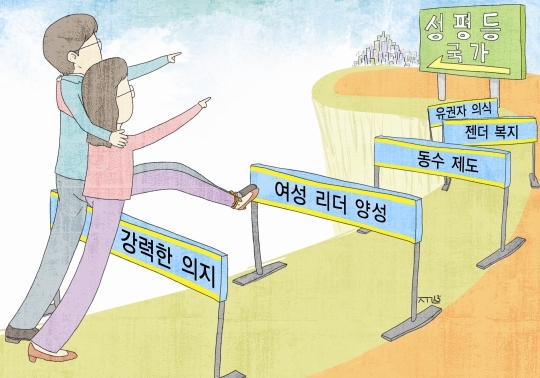

<7 tasks to achieve gender equality in Korea>

1. Muster a strong political will

2. Nurture and support female politicians

3. Introduce a Korean version of “La Parité”

4. Build a gender welfare regime

5. Raise female voters’ awareness

6. Urge politicians to have a stronger sense of responsibility

7. Give more power to the organization that handles women’s policies

Cho Hye-young: Although we have elected a female as president for the first time in our constitutional history, it is still too early to determine whether this administration is delivering on our expectations on building a gender equal state. The aim of today’s forum is to come up with ideas on what we specifically have to do in order to achieve gender equality in Korea, and it is an opportune time as more people are closely watching women in politics nowadays with the upcoming municipal elections. Director Kim Eun-kyung will introduce with specific examples the French cabinet where the number of men and women is required to be equal; executive director Kim Eun-ju, women’s policies in Germany; and prof. Choi Yeon-hyuk, gender equal politics in Sweden. Afterwards, Head of WSWS Shin Pil-kyun will discuss ‘a gender equal state and a welfare state’ and prof. Kim Hyung-jun will discuss ‘gender equal state and democracy.’ We’ll also gather our heads to draw the roadmap to achieve gender equality in Korea. Director Kim, please take the floor and give your presentation on the French cabinet and the equal number of both genders.

France

How did they achieve a gender equal cabinet

Kim Eun-kyung: Until 1997, the ratio of women in politics was similar to that of Korea. It isn’t so any more. The levels of gender equality and women’s participation in many sectors of the society in Korea and France are significantly different. As of 2013, women represent 26.9% of the French National Assembly, while only 15% of Korea’s National Assembly is women. When the provision on equal representation of either gender was deemed unconstitutional and struck down in 1982, it was a moment of crisis for female participation in politics. After doing away with the ‘quota’ system, the idea of ‘parity’ began to gain support as a measure to achieve ‘equality,’ one of the universal values that the French republic upholds. The reforms made to the constitution in 1999 and relevant provisions in 2000 finally made sure that both men and women can run for elected offices.

France’s 2012 presidential election made the Socialist Party’s François Hollande as president, who soon formed a cabinet comprised of 19 male and 18 female ministers, the first gender equal cabinet in the history of the republic. Also, the Ministry of Parity and Professional Equality was re-established as an independent body after 2 decades. The gender equal cabinet is a means to build an equal society rather than the end itself, since the basic idea behind this is that both men and women have the right to take part in running a country.

That is why what this gender equal cabinet can do and has been doing is so important. This cabinet submitted a bill for gender equality law this January, the first fundamental law to support equality in every part of the society, which passed the senate. The law includes specific measures and policies that the central and local governments as well as public institutions gathered their heads together to come up with. A consultative group, formed during the process, discussed practical measures and solutions for the relevant issues and presented the outcome through the bill.

The credit of creating this bill goes entirely to the gender equal cabinet. It shows that the cabinet considered achieving gender equality as one of the core agendas that the government must take care of. They needed a law in order to solve France’s numerous problems including women and housework, women in the workforce, and women representatives, and having the same number of men and women in a cabinet can be an effective way to utilize law to support equality.

A broader application of the principle to ensure either gender gets the same amount of access through measures like ‘La Parité’ and the gender equal cabinet is historically significant since it replaced meaningless debates with sexists and misogynists with discussions on justice, democracy, and economic growth based on equality. It seems that the policies based on the advocacy for having equal number of either gender in various walks of the society must have brought the debate onto a whole new level.

Compared to the progress made in France, however, Korea, where only two of the ministers are women, still has a long way to go until we achieve gender equality. We have all the more reason to push it as a national agenda now that we have a female as commander-in-chief. Also, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family could do better. Putting women’s issues on a consistent line and trying to find causes and effects out of them is important. The MOGEF doesn’t seem to be pondering much over bringing gender equality and justice through fundamental changes. Their attempts to deal with only the visible problems would end up wasting their time and money. What they should do is to thoroughly examine the reality and tackle the root causes. They should keep in mind that violence and discrimination against women are chronic problems that resulted from the lower status of women.

Cho Hye-young: Thank you for the very insightful comment that forming gender equal cabinet and bringing gender equality are a matter of justice involving a huge shift of paradigm. Now, Director Kim Eun-ju will share the examples of Germany.

Germany

Political Parties Take the Initiative

Kim, Eun-ju = The hottest issue during Germany’s general election was female Chancellor Angela Merkel’s third-term victory. She successfully overcame two hurdles: growing up in the former “East Germany” and being a “woman.” Within Germany, Merkel is perceived as a benevolent conservative, with an affectionate nickname Mutti (mother), boldly pushing for pragmatic policies such as shutdown of nuclear power plants and expansion of welfare benefits. In the European Union, on the other hand, she is a chancellor who strongly demands Southern European nations to take austerity measures, which gave her another nickname, Frau Nein (not a woman).

In the 2013 German general elections, 229 out of 630 elected lawmakers were women, taking up 36.3%. This figure is an increase from 32.8% in 2009. What drives women’s political participation in Germany is the quota system that the political parties adopted voluntarily. Starting with the Green Party (50% quota) in 1986, Social Democratic Party followed suit to introduce its own quota (40%) in 1998 and the Left Party (50%) in 2007.

Thanks to a well-established party democracy, political parties serve as an important window for women to wield political influence. Political parties’ active engagement has made the quota practice close to mandatory, and this has been bringing out women’s participation in politics.

La Parite movement in France was in fact a movement that took place in the entire Northern Europe. One commonality in advanced democracies including Germany, Sweden, and France is that they have been working to achieve “equity by parity.” In fact, “equal right to leadership” is an undoubted right, guaranteed through the concept of parity or 50%, not because it is an act of charity for women who are socially weak, but because this right reflects a given fact that all humans are either male or female.

While controversy over basic recommendation still continues as we near the regional elections next year, why don't we suggest legal and institutional revisions to ensure parity among elected officials. Basic local assemblies mainly deal with issues closely related to daily lives, and women’s expertise and participation in these bodies carry utmost importance. Thus, abolishing systems that promote female representation, such as political parties’ recommendation, quota, and proportional representation, can become a significant obstacle in the development of local governments since such act will only result in reduced participation of women. Enhanced representation of women is a matter that concerns not only women’s empowerment, but also the development of local autonomy. Therefore it is necessary to devise means to expand women’s participation at a local government level.

We need to embark on a movement to reform relevant laws and institutions that will bring about not just a strengthened quota, but gender parity to ensure equal rights to leadership. A new movement, that is, a gender parity movement is necessary to encourage all people across the society, regardless of gender or age, to pursue and practice gender equality not as a feminist value but as a universal one. I hope that we start engaging in a gender parity movement. If the recommendation system stays, then we can demand gender parity be incorporated in the recommendation process, and if it is repealed or earns a grace period, have it incorporated in the election system through reform.

Cho Hye-yeong = While I was in Sweden to cover this case, I asked an official from the Ministry for Gender Equality whether government bodies reached agreement smoothly on this matter. The answer was that the Ministry for Gender Equality’s position stands way beyond other ministries. This made us quite shameful since in our case, the Minister of Gender Equality cannot even convene other ministers for a meeting. Next, Professor Choi Yeon-hyuk will explain to us how policies are implemented in Sweden.

Sweden

Varannan Damernas (“Every other seat for women”)

Choi Yeon-hyuk: In the 2000s, women constituted 47% of the members of parliament in Sweden, the highest parliamentary representation of women in the world. The percentage of women ministers has reached 50% since the mid-1990s with 11 out of 22 ministerial positions filled by women. Such high female representation in politics is symbolic as women ministers oversee important policy sectors including foreign affairs, trade, judicial affairs, and social welfare. Swedish women hold positions of power at the national as well as the municipal level with female representation in the municipal council and the local elected assemblies standing at 47.5% and 42%, respectively.

The gender equality policy of Sweden is represented by “Varannan Damernas,” which means “every other seat for women.” This principle is at the center of the Swedish government’s national agenda aimed at becoming a country with the greatest gender equality and has been applied to all policy sectors ever since.

No country in the world can realize a perfect, gender-equal society from the very beginning or drastically change the deep-rooted, male-centered social structure overnight. Most countries gradually change through institutionalization. The awareness and commitment of the political parties, the government, and the academia regarding gender equality played a decisive role in changing the once male-dominated politics in Sweden to one with more equal representation. Above all, the role of the political parities was crucial and cannot be over-exaggerated.

What’s more important than equal representation of both genders is practical empowerment of women, i.e. the actual sharing of power and responsibility. Those who are involved in politics in Sweden and Northern Europe are trained from early on since they become party members during their youth. So these young women start from the assemblies or the municipal council and climb up the ladder to become council members or some are singled out from the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League to serve as council members for 5~6 years. Later these young women become ready and well-trained to fill the ministerial positions in Sweden. As such, the political parties play an important role in nurturing talented women and serving as a gateway for these women to reach positions of power. These political parties were at the core of the driving force that led to the changes in Sweden. Swedish women were given their due share of power by filling some of the positions with actual authority. However, ensuring that women have equally important positions is more crucial than simply guaranteeing the same number of positions for both genders. This is much more valuable. Also, equally important to sharing power is sharing the responsibility. Female empowerment should go hand in hand with the division of responsibility.

Sweden no longer considers women’s rights issue as a matter of discrimination but rather approaches it from a social inclusion perspective. Thus, the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs is responsible for policies on women’s rights. Discrimination against women, immigrants, and the disabled, which were dealt separately in the past, is now handled from a holistic perspective since no member of the society should face discrimination.

As efforts to mainstream gender equality into all policy sectors gained momentum from the late 1980s and early 1990s, all ministers are now obligated to evaluate the gender equality efforts of each department. Such evaluation has a powerful influence on the overall evaluation of the current government. In Sweden, the Deputy Prime Minister is directly involved in gender equality policies. Likewise, the Korean government should elevate the status of the Minister of Gender Equality and Family to the Deputy Prime Minister level and grant substantial authority.

Kim Eun-kyung: We need to be more critical of those who raise issue with the qualification of the female political leaders. It depends on which criteria you apply. If we were to realize equal representation in terms of number, we need to ensure equal proportion of both genders. There can be incompetent men among the 50% so why raise issue with only the women?

Choi Yeon-hyuk: I mentioned that the degree of gender equality is more important than numbers. We can’t simply match the numbers without considering the competency of the candidates. We need to appoint well-educated women who are ready for such positions. That’s why it is important to nurture talented women who are armed with political knowledge and a strong sense of service to society, so that they can fill the government positions.

Kim Eun-kyung: Politics isn’t for everyone whether it is men or women. What I mean is that we should ensure equal representation of qualified men and women in politics.

Shin Pil-kyun: We should take note that equal representation in the French parliament was a means not an end in itself. I’d like to know more about the background and causes of such change in France.

Kim Eun-kyung: The changes in France did not occur all of a sudden. The ruling of the gender quota law as unconstitutional sent shockwaves across the feminist circle in 1982. Afterwards, female politicians and philosophers engaged in a wide range of rallies, research, and social discussions for over a decade and finally accomplished the amendment of the constitution in 1999. After the legislation on gender quota came into effect in the 2000s, the equal number of women were elected to the local councils, thereby bringing about substantial changes. Also, the rising female political leaders of today did not come to stardom overnight. Rather, they have been involved in politics since in their twenties. In that sense, the changes in France will continue on for some time.

Shin Pil-kyun: The fact that the French amended their constitution is very meaningful. However, although there might be equal representation in the organizations, it might not be the case in everyday life. Also, such change could have been possible since France has a mature democracy. It could take some time for Korea to adopt the French model.

Kim Eun-ju: In fact, the representation of women in politics was not that high in Europe before the enactment of the legislation on gender quotas. Legislation is what led to drastic changes and thus, higher female representation. Since the enactment of the legislation, equal number of men and women candidates had to be on the political party's lists, which eventually led to higher representation of women in French politics.

Cho Hye-yeong: I wish there were some numbers that show the success rate of such legislation. It’s regretful that we cannot easily relate to the cases in Northern Europe because in Korea, enactment of a law is one thing whereas the implementation of the law is another. I think what Shin pointed out is that we need to consider if such mandatory quota can be sustainable and it’s more important to change the culture and the customs of our society.

Welfare State, Women Systemically Breaking out of Poverty

Shin Pil-kyun = For the Korean society to become a country in which men and women are equal, establishing a welfare state is the only path. “What kind of welfare state should it be?” is the important point we need to ponder. And, it should be a one that has carried out innovated improvements for gender-related social policies.

If we take a close look at the relationship between social policies and gender equality in major welfare states among OECD member countries, especially in the realm of family policies reflecting labor market policies, one thing stands out: parental insurance system. The total cost necessary per one infant (age 0 ~ 3), including cost of parental leave and childcare services, accounts for 53% of per capita GDP in Northern Europe (59.4% in Sweden), much higher than 22% in continental countries. Another difference is the paternal leave which lasts, on average, for 6.7 weeks (10 weeks in Sweden). This is 4 times longer than the OECD average of 1.7 weeks. They explain how gender equality is promoted in childcare and house works.

Tax break is another example. If total income of a married couple is the same as the income of a one-earner household, tax policies provide more benefits to households with two income earners. Thus, this policy aims to achieve gender equality by encouraging women to participate in the economy.

The next issue involves women’s breaking out of poverty. In regards to the influence of family policies on poverty rate, the discrepancy in poverty levels among countries is subtle before income redistribution, but it gets greater once income is redistributed. The poverty rate in terms of disposable income in Sweden is exceptionally low, incomparable to other nations. Furthermore, there is not much difference between households with a single parent and two parents. In this sense, contents of family policies and how far institutions reach in each country helps us estimate how much of the gap is reduced between social classes. This bears significant implications for preventing women’s poverty. Aside from family policies, pension system also serves as another key welfare policy that can stop elderly women from falling into poverty.

In Sweden, the employment rate of women with children, particularly those with infants, is only 10% lower than that of average women. However, the gap is more distinct in other countries, the same rate falls much lower when compared not only to women with children under age 16 but also to women under age 50. Countries with low fertility rate tend to have low employment rate of women with children, and those with high fertility rate have high female employment rate. This clearly exemplifies the effects of “two income earners model” that provides long paid parental leave, return-to-work guarantee, childcare services and facilities that satisfy the demands and desires of families, and tax policies.

As we have seen from the social policy examples, especially the family policies introduced by the OECD member nations and their effects, a shortcut to alleviate social and economic inequality is women’s breaking out of poverty in a systemic way. To this end, opportunities for women to get jobs and engage in economic activities should be given equally. In other words, this is a policy on work-family balance. If equity between men and women is established across the society and women systemically escape from poverty, we can successfully build a society with gender equality.

Cho Hye-yeong = Representative Shin Pil-kyun has shared his thoughts about how we should focus more on values in relation to this forum’s theme, “The answer is gender parity.” We have the tool, gender parity. The question is which goal we should pursue using this tool. We have discussed important issues from party politics to how a nation with gender equality is along the same line with welfare state. Party politics has its basis on democracy, and in previous meetings, we talked about “equal democracy” necessary for advancing toward a country with gender equality. Some even suggested that we call this “gender democracy” instead. We will now ask Professor Kim Hyung-jun to share his opinions on this matter.

Kim Hyung-jun = Overall, we all seem to agree on the direction that “we should establish gender equality in the society.” That said, we should place particular interest in why we cannot go in that direction. There are two reasons for this. First, there is no female influence in politics, and second, politicians as a matter of fact don’t have any willpower to achieve gender equality.

The situation we are in is largely distorted. Political parties exist, but do not function properly. Civic groups need to play their parts, but they have become a new power, and so have women advocacy groups. They do put a certain level of effort but don’t devote themselves entirely to their works.

If we take a look at the political attitude of voters in the last year’s election, female voters were completely sidelined when they were supposed to be the driving force. Without enhancing women’s participation, social and family policies are useless. Women’s active participation fails to surpass that of men, and women cannot exert any political influence on non-regular issues although they involve women in general. If women cannot wield power in politics to bring all these together, scholars in women’s studies or activists should take the job instead. This is not happening either.

Lawmakers lack autonomy and responsibility, and have low level of representation. This is primarily due to the absence of fairness that guarantees all these values. Consequently, current state will soon collapse without complete overhaul of the National Assembly, lawmakers’ autonomy, and NGOs’ recovery of their original functions.

Achieving gender equality requires at least 30 years. I would like to suggest we search for a solution that will create a butterfly effect instead of trying to do everything at once. In my opinion, the answer is normalizing political parties through elections. Rather than debating over basic recommendation system, I believe it could be better if we adopt proportional representative system like Sweden and abolish the single member district system. Until now, women were not successful in exercising their power in politics. Therefore, the top priority should be refreshing awareness of lawmakers. It should come to their mind that good politics is possible when they are close to voters and favorable to women.

Through the last policy evaluation in the National Assembly, 8 female lawmakers were included in the top 20 list. This is a remarkable result considering that women politicians take up much fewer seats. However, all these women failed in the next election. Who would attempt to introduce family policies when policies and political career are completely different matters in the current environment? In this situation, it does not make sense to blindly bring in practices from other nations. We should first fix our unreasonable political structure. We should prepare for the most feasible long-term plan.

Country with Gender Equality Means Realizing Equal Democracy

The Crucial Task of Empowering Women in Politics

Choi, Yeon-hyuk = The voting rate among the young Swedish women with two to three children went up after the government introduced family-friendly policies and childcare policies for working mothers. Welfare benefits allowed women to become more interested and aware of social issues, guaranteed them more social participation, and increased social responsibilities and efficacy through sharing of responsibility and authority. Another attribute of the Swedish model is that although the overall institutional reform took place gradually over 30 years, the momentum for key changes were created by the active efforts of the progressive politicians. Politicians are the ones who can actually drive policy changes to make them more women-friendly, and raise the number of female proportional representatives. Thus, if they are not interested in reforming policies, a crucial task becomes how to address these issues.

Shin Pil-kyun = Finding the most effective way to do so is the key. Can a gender-balanced cabinet achieve this? Will the welfare policies make it possible? We must now move beyond these basic questions and continue with the discussions on how we will prioritize the methods and what method would be the most crucial.

Kim Hyung-jun = The female members of parliaments are neglecting their duties. They do not realize that they represent women. Once they become proportional representatives, they become just another politician who follows the orders of the party leaders. Female politicians should get together and discuss about policies for gender equality, but such discussion is not happening.

Choi Yeon-hyuk = Drawing a long-term roadmap is crucial in a reform. The momentum for step-by-step development should be created based on the roadmap. So who will create such momentum and how? In 1974, when the Social Democratic Party was leading Sweden, parental insurance program was introduced. In 1991, subsequently, the act on equal treatment between men and women at work was enacted. Again, institutionalization created the momentum in this case.

Kim Hyung-jun = At the Forum on Gender Equal Countries, we discussed what should be introduced or fixed to send requests to legislators later on, and set priorities for the next year. More of such channels for citizen participation will reduce the time needed for reform from 30 years to 20 or even ten years.

Kim Eun-kyung = Creating as much controversy as possible is critical. It is not enough to have only five members at this forum. Female politicians and activists should be provided with more opportunities to participate in these events and think about the relevant issues.

Cho Hye-yeong = The most needed elements of becoming a country with true gender equality would be strong willingness of the government, a dedicated leader in women’s movement, political institutions that guarantee representation of women, and establishment of welfare benefits based on gender equality perspective.

Kim Hyung-jun = Gender equality cannot be built without the autonomy and a sense of responsibility of the legislators. In addition, the enhanced social awareness of female constituents, as well as the structural reform to bring women out of poverty are needed.

Shin Pil-kyun = Our discussion has mostly focused on the authority, but addressing women’s issues should also be about resolving the real-life challenges that women face. Women benefit from the practical policies that improve their quality of life. We need to bring the pragmatic issues to surface now. Inequality still remains intact in many parts of the society.

Kim Eun-ju = What allowed German Chancellor Angela Merkel to win her third term with a higher approval rating from women than men was that she let go of her conservative ideology and values at times and actively adopted pragmatic policies to resolve issues. I believe that is the direction a successful female head of state should take. Modern German society teaches us about two things: the accumulation of political competence, and the reform of party structures. Political parties are a part of the people’s lives. Germans join political parties at young age, run for municipal elections later on, and naturally build their political competence in the process, which strengthens the foundation of their party politics.

Establishing a comprehensive consultation system

Kim Hyung-jun = Adding on to the point about party politics, it is also important to make people feel the actual benefits of gender equality in their daily lives. Swedish women can feel that their social participation brings benefits to them and changes the world, whereas Korean women can hardly feel such impact. People should be able to feel the specific and practical impact of policies in their lives. Only then will women be motivated to move and participate.

Kim Eun-kyung = The changes in France were based on meticulous analysis of reality. Politics reflects the reality of a society, but Korea does not have an accurate analysis of its current status. The solutions for this are a comprehensive women’s policy and policies for gender equality. Building a cooperation system across various government bodies is crucial.

Choi Yeon-hyuk = Philosophical review should be done as well. Popular sovereignty should be our philosophical basis. Moreover, considering that half of the citizens are women, the equal value of people as individuals as well as groups should be respected. The society should also pursue civil, political, and ultimately, social rights. In the process, we need an education that teaches our people to pursue equal rights starting at a young age. It is important to allow people to experience the civil virtues since childhood. Not only the childhood education, but also lifelong education is imperative.

Cho Hye-yeong = We looked into the challenges for Korea in order to achieve gender equality. The seven challenges we identified today require continued discussion to be addressed through detailed measures. Women News will work with the five representatives of the National Forum on Gender Equality and add more participation from the political, civil, and academic circles, to be in the lead of drawing a concrete picture for gender equality in Korea.